Billion-Story Building

My daughter—age 4.5—maintains she wants a billion-story building. It turns out not only is that hard to help her appreciate this size, I am not at all able to explain all of the other difficulties you'd have to overcome.

Keira, via Steve Brodovicz, Media, PA

Keira,

If you make a building too big, the top part is heavy and it squishes the bottom part.

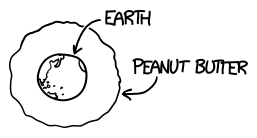

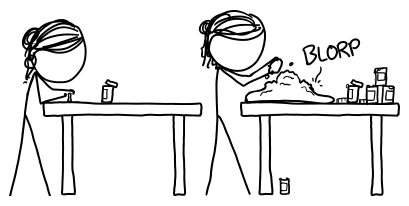

Have you ever tried to make a tower of peanut butter? It's easy to make a little tiny one, like a blobby castle on a cracker. It will be strong enough to stay standing. But if you try to build a really big castle, the whole thing smushes flat like a pancake.

The same thing happens with buildings. The buildings we make are strong, but we couldn't make one that went all the way up to space, or the top part would squish the bottom part.

We can make buildings pretty tall. The tallest buildings are almost 1 kilometer tall, and we could probably make buildings 2 or even 3 kilometers tall if we wanted, and they would still be able to stand up under their own weight. Higher than that might be tricky.

But there would be other problems with a tall building besides weight.

One issue would be wind. The wind up high is very strong, and buildings have to be very strong to stand up against the wind.

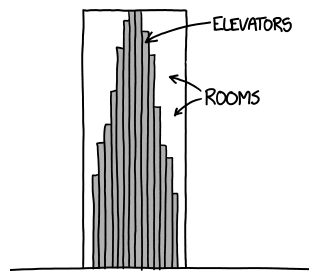

Another big problem would be, surprisingly, elevators. Tall buildings need elevators, since no one wants to climb hundreds of flights of stairs. If your building has lots of floors, you need lots of different elevators, since there would be so many people trying to come and go the same time. If you make a building too tall, the whole thing gets taken up by elevators and there's no space for regular rooms.

Maybe you can think of a way to get people to their floors without having too many elevators. Maybe you could make a giant elevator that takes up 10 floors. Or you could make fast elevators that work like roller coasters. Or you could fly people up to their rooms with hot air balloons. Or you could launch them with catapults.

Elevators and wind are big problems, but the biggest problem would be money.

To make a building really tall, someone has to spend a lot of money, and no one wants a really tall building enough to pay for it. A building many miles tall would cost billions of dollars. A billion dollars is a lot of money! If you had a billion dollars, you could rent a giant spaceship, save all the world's endangered lemurs, give a dollar to everyone in the US, and still have some left over. Most people don't think giant towers a few miles tall are important enough to spend a lot of money on.

If you got really rich, so you could pay for a tower to space yourself, and solved all those engineering problems, you'd still have problems making a tower a billion stories tall. A billion stories is just too many.

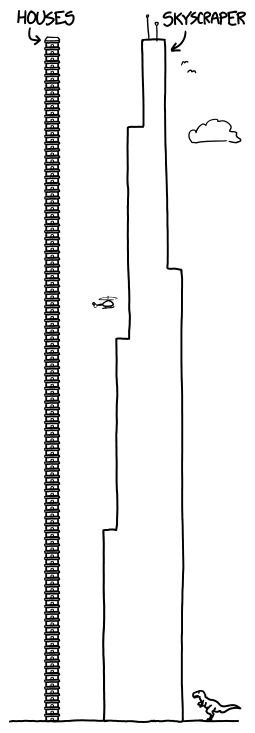

A big skyscraper might have about 100 floors, which means it's as tall as 100 little houses.

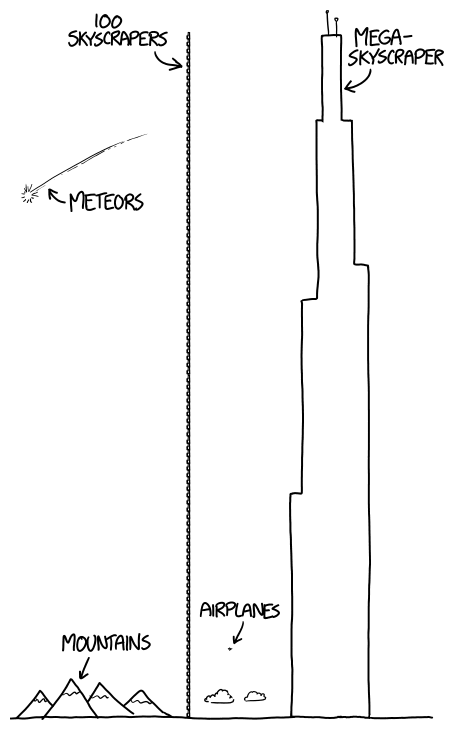

If you stacked 100 skyscrapers on each other to make a mega-skyscraper, it would reach halfway to space:

This skyscraper would still only have 10,000 floors, which is way less than your billion floors! Each of those 100 skyscrapers would have 100 floors, so the whole mega-skyscraper would have 100 times 100 is 10,000 floors.

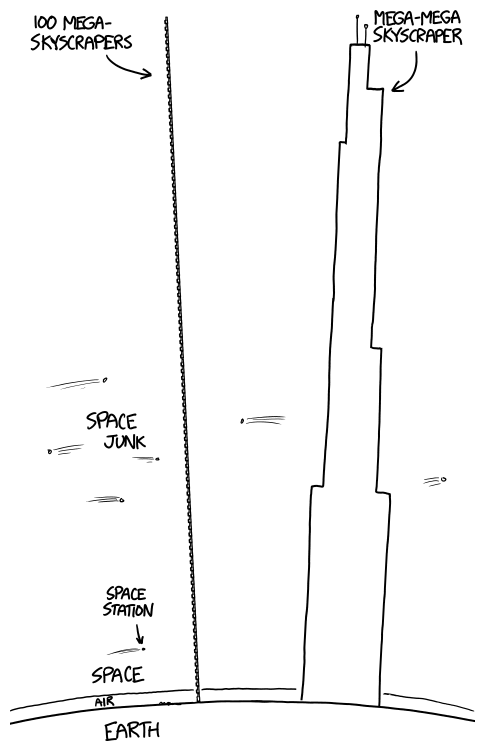

But you said you wanted a skyscraper with 1,000,000,000 floors. Let's stack 100 mega-skyscrapers to make a mega-mega-skyscraper:

The mega-mega-skyscraper would stick out so far from the Earth that spaceships would crash into it. If the space station were heading toward the tower, they could use its rockets to steer away from it.[1]They'd probably get pretty grumpy after having to dodge your tower repeatedly, so you might want to launch fuel and snacks out the window with a rail gun as they go by. The bad news is that space is full of broken spaceships and satellites and pieces of junk, all flying around at random. If you build a mega-mega-skyscraper, spaceship parts will eventually smash into it.

Anyway, a mega-mega-skyscraper is only 100 times 10,000 = 1,000,000 floors. That's still a lot smaller than the 1,000,000,000 that you want!

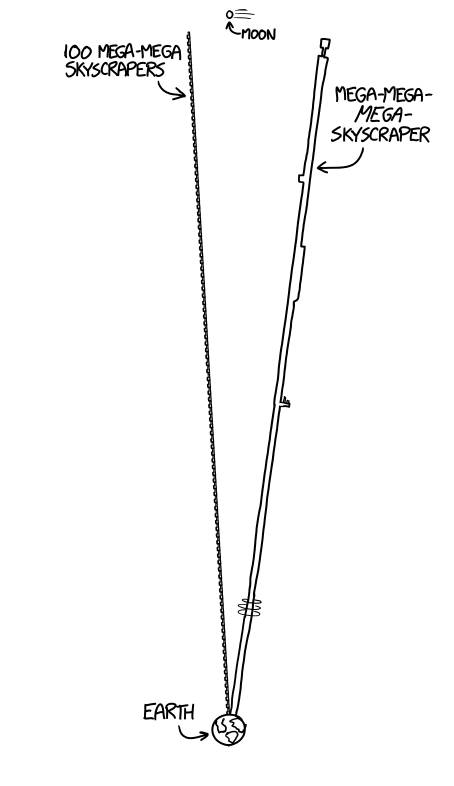

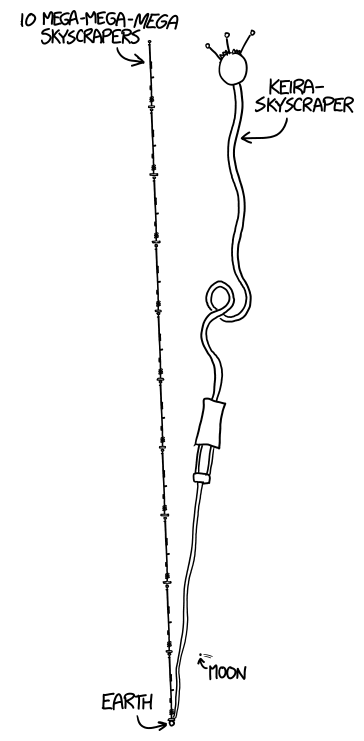

Let's make a new skyscraper by stacking up 100 mega-mega-skyscrapers, to make a mega-mega-MEGA-skyscraper:

The mega-mega-MEGA-skyscraper would be so tall that the top would just barely brush against the Moon.

But it would only be 100,000,000 floors! To get to 1,000,000,000 floors, we have to stack 10 mega-mega-MEGA-skyscrapers on top of each other, to make one Keira-skyscraper:

The Keira-skyscraper would be pretty close to impossible to build. You would have to keep it from crashing into the Moon, being pulled apart by the Earth's gravity, or falling over and smashing into the planet like the giant meteor that killed the dinosaurs.

But some engineers have an idea sort of like your tower—it's called a space elevator. It's not quite as tall as yours (the space elevator would only reach partway to the the Moon), but it's close!

Some people think we can build a space elevator, but other people think it's a crazy idea. We can't build one yet because there are some problems we don't know how to solve, like how to make the tower strong enough and how to send power up it to run the elevators. If you really want to build a gigantic tower, you can find out more about some of the problems they're working on, and eventually become one of the people coming up with ideas to solve them. Maybe, someday, you could build a giant tower to space.

I'm pretty sure it won't be made of peanut butter, though.